Continued from Part 1

It seemed banishment was unlikely to stop the pugnacious Roger Williams, so a scheme was hatched to kidnap him and place him on a ship back to England where he would surely be imprisoned, if not executed, once they explained his crimes to the King. His old friend John Winthrop, who had publicly condemned Williams and called for his banishment, secretly sent a message to Roger to flee with instructions on how he might reach the winter camp of Ousamequin.

There was a fearsome blizzard blowing outside, and the coastal waters were frozen over from Cape Cod to Narragansett Bay, so passage by boat was rendered impossible. But knowing the Sheriff could arrive at any moment, Roger Williams left his wife Mary, and their new baby girl, Freeborn Williams, and started his long journey by foot towards the Wampanoag camp.

Wandering in the wilderness of what is now Rhode Island, the nearly frozen Williams was rescued by a Native hunting party, who took him to Massasoit Ousamequin. He was heartily welcomed by his friend the chief and stayed in the Wampanoag camp until springtime had sprung.

Williams, with the support of his allies in Boston, first purchased land from the Wampanoag on the east bank of the Seekonk River, but Ousamequin brought word from their mutual friend William Bradford that they were on land officially considered part of the King’s charter. Apparently, his enemies were already planning to invade and destroy his small settlement.

Therefore, Roger Williams knew he would need to reacquaint himself with the Narragansett across the river. He and men from the settlement borrowed canoes from the Wampanoag, and left to reconnoiter the land of the Narragansett. Legend says, as he approached an outcrop called Slate Rock, upon it stood a party of Narragansett who cheerfully welcomed him, shouting in broken English, “What cheer, Netop?”, translated as “What’s up, My Dude?!”

Massasoit Canonicus, the great chief of the Narragansett, and Sachem Mianinomi, met with and were impressed by Roger, who knew their ways and was fluent in their language. A deal was soon struck, and Williams was offered land with a freshwater spring next to the Great Salt Cove.

The settlement was named Providence, as Roger believed providence had brought them to this place. There were a handful of men who joined him from the original settlement on the Seekonk, but soon boats were arriving with families from the Massachusetts Bay Colony and beyond.

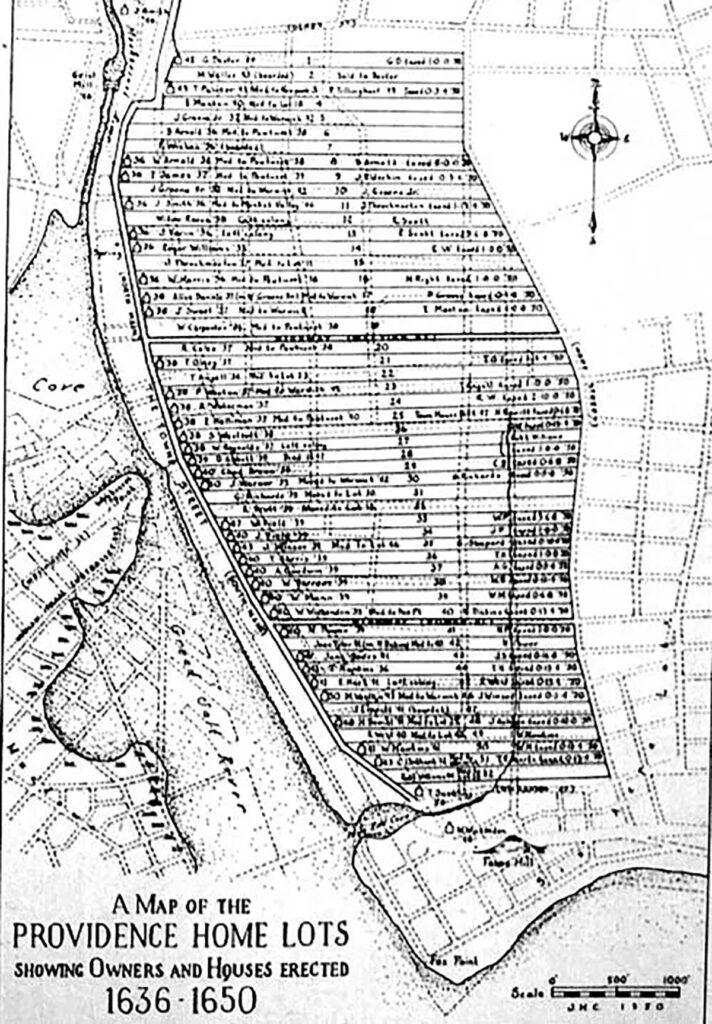

Williams designed the layout of the town so every parcel was of equal size. On top of that, every parcel had a piece of waterfront, a piece of hill front and a piece of flatland, with one common road. When governmental decisions were to be made, every head of household had a vote, even if they were women. This was Roger Williams’ plan for a utopian community. A place of equality, free market, and freedom from the tyranny of the Boston authorities and the King in England. I’m picturing him in a pilgrim hat, thigh-high buckle boots, and an An-cap hoodie.

This stand on equality was soon tested by Joshua Verin, ropemaker, and his wife Jane. In Salem, Joshua and Jane had been censured for lack of church attendance, which in the Puritan colony could lead to severe punishment. Verin was one of the original colonists to move to Rhode Island with Williams, and is said to have been in the very boat with Williams when they met the Narragansett at Slate Rock (see famous image above).

Providence did not have a church building, so services were held in the Williams’ home. Just south of Williams lived John Throckmorton and family, and the Verin’s were Williams’ neighbors to his immediate north. Jane Verin became a regular attendee of Williams’ services, until she wasn’t.

Missing her presence, neighbors went to check on Jane, only to find her husband had beaten her nearly to death. Her decision to return to church without his approval had triggered his terrible temper.

Now, women had extraordinary rights in separatist congregations (for the day). Take the conventicles of Anne Hutchinson for example. Yet, even with these outliers, women were still considered subservient to men, and also there were no civil laws against spousal abuse unless death or maiming occurred. But the leaders of this Providence community felt something needed to be done, so they called a meeting.

At this meeting, there was a faction who believed Joshua Verin had every right to beat his wife for disobedience. Still, the consensus was that despite Verin’s right to beat his wife, the ropemaker had interfered with Jane’s right to decide whether or not she would attend church services, and that was a bridge too far! For suppressing Jane’s “liberty of conscience” Joshua Verin lost his voting privilege.

Unfortunately for Jane, the couple quit the Providence community and returned immediately to Salem. Roger Williams petitioned the authorities in the Massachusetts Bay Colony for their assistance in the matter, to no avail, and the last we hear of Jane Verin she was tried for non-attendance to Salem Church and ejected from the congregation. Her husband Joshua Verin was to later remarry in Barbados, so we can surmise.

Genealogical note: Catherine Marbury Scott, the youngest sibling of Anne Marbury Hutchinson, and her husband Richard Scott moved into the Verin home once it was vacated. These are my wife’s direct ancestors (as were the Throckmorton’s), and we’ll be addressing them further in a separate blog post.

Despite the occasional tragedy, the settlement of Providence Plantations grew. Joined by Dr. John Clarke and Ezekial Holliman, Roger Williams would bring a revolutionary religious fashion to New England. To further separate themselves from the Church of England and the Roman Catholics, they turned their backs on the tradition of christening babies into the Faith and called for adult baptism by immersion. In 1638, Holliman, who was banished from Boston for heresy, baptized Roger Williams, and soon after they built the First Baptist Church, which indeed was the very first in America.

After Anne Hutchinson was banished from Massachusetts in 1638, Roger helped the Hutchinson’s and their followers negotiate with the Narragansett for a spot to establish their settlement of Portsmouth. For more on this, see my coming blog post Anne Hutchinson Part 4.

Roger Williams remained a friend to the Native peoples, and built a trading post which was his primary source of income. During the Pequot War, the colonies who had banished Williams, begged for his assistance. Using his connections, he convinced the Narragansett to fight against the Pequot, and after vanquishing the Pequot, he and the Narragansett decided the fate of those remaining of the tribe.

To make his colony official, Roger Williams left Providence and sailed for England, which was now in their Civil War. King Charles was no longer the head of England having been literally beheaded by the followers of Oliver Cromwell.

There Williams petitioned the good friend of his allies, the Hutchinson’s, and received his Charter from the offices of Lord Henry Vane the Younger, now a leading Parliamentarian. After being banished from Massachusetts Bay for his support of Anne Hutchinson and John Wheelwright, Lord Vane returned to England to support his and Wheelwright’s good friend Oliver Cromwell. Vane did not participate in the King’s “removal”, but was he partially responsible? Most likely.

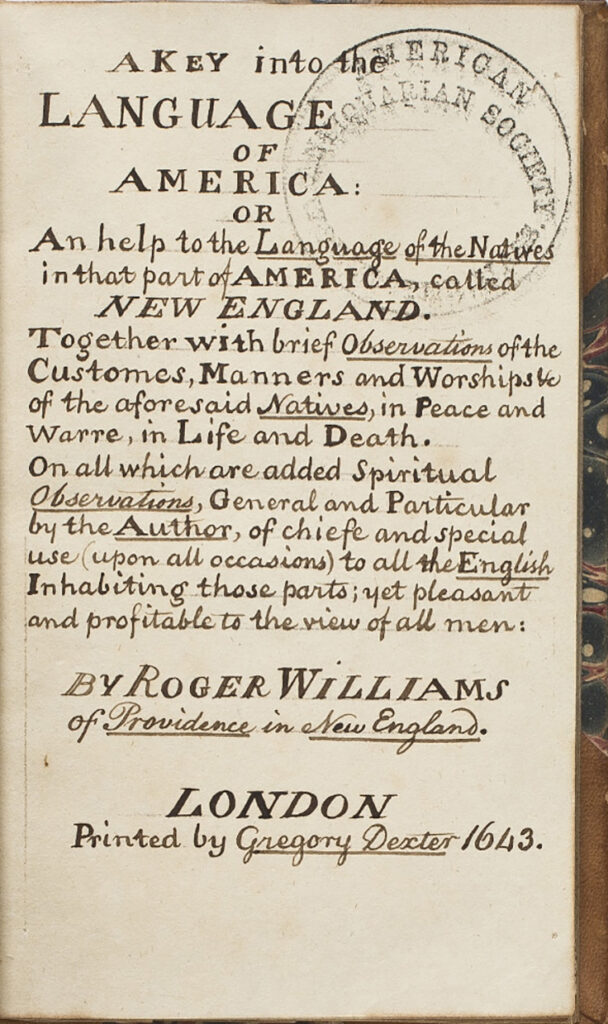

Meanwhile, Roger Williams published the Algonquian language book we previously discussed as well as his most famous book The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience which would later be burned publicly by the House of Commons.

Roger became reacquainted with an old schoolmate from his days at Cambridge, John Milton, who published his Areopagitica the very same year as The Bloudy Tenant (1634). Roger taught Milton to speak Dutch, one of at least five languages in which Roger was fluent, but with the uproar over his newest book now outweighing the popularity he had gained from A Key to the Language of America, Roger decided to skedaddle back to New England.

There is plenty more to be said about Roger William’s life, but that would take a novel. At the age of 70 when most of his Native friends had gone on to the “happy hunting ground”, war came to Roger’s door in the form of King Philip, whose war will be discussed in another blog post. Williams led the Providence militia, but the Wampanoag and even many of the Narragansett were against them now. Providence was burned, including the Williams’ home.

Unlike so many of the colonists and Natives involved in King Philip’s War, Roger Williams did survive for a while longer, passing in March of 1683. He was buried on his homesite and the grave eventually lost, but years later an attempt was made to find his burial location. He was moved to a family crypt, then in 1936 on the 300th Anniversary of the founding of Providence, Roger’s remains were removed to Prospect Terrace where you can visit his memorial today.

One last note, a statue of Roger Williams stood in the US Capitol Rotunda for many years until it was removed to the basement to make room for busts of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Lucretia Mott. As someone who was against idols of any kind, and an occasional proponent of Women’s Rights, maybe he would be okay with that.